Welcome

“The sculptor cannot merely carve forms, but he must reveal the active forces in the material and in nature, which stretch the visible surfaces from within.”

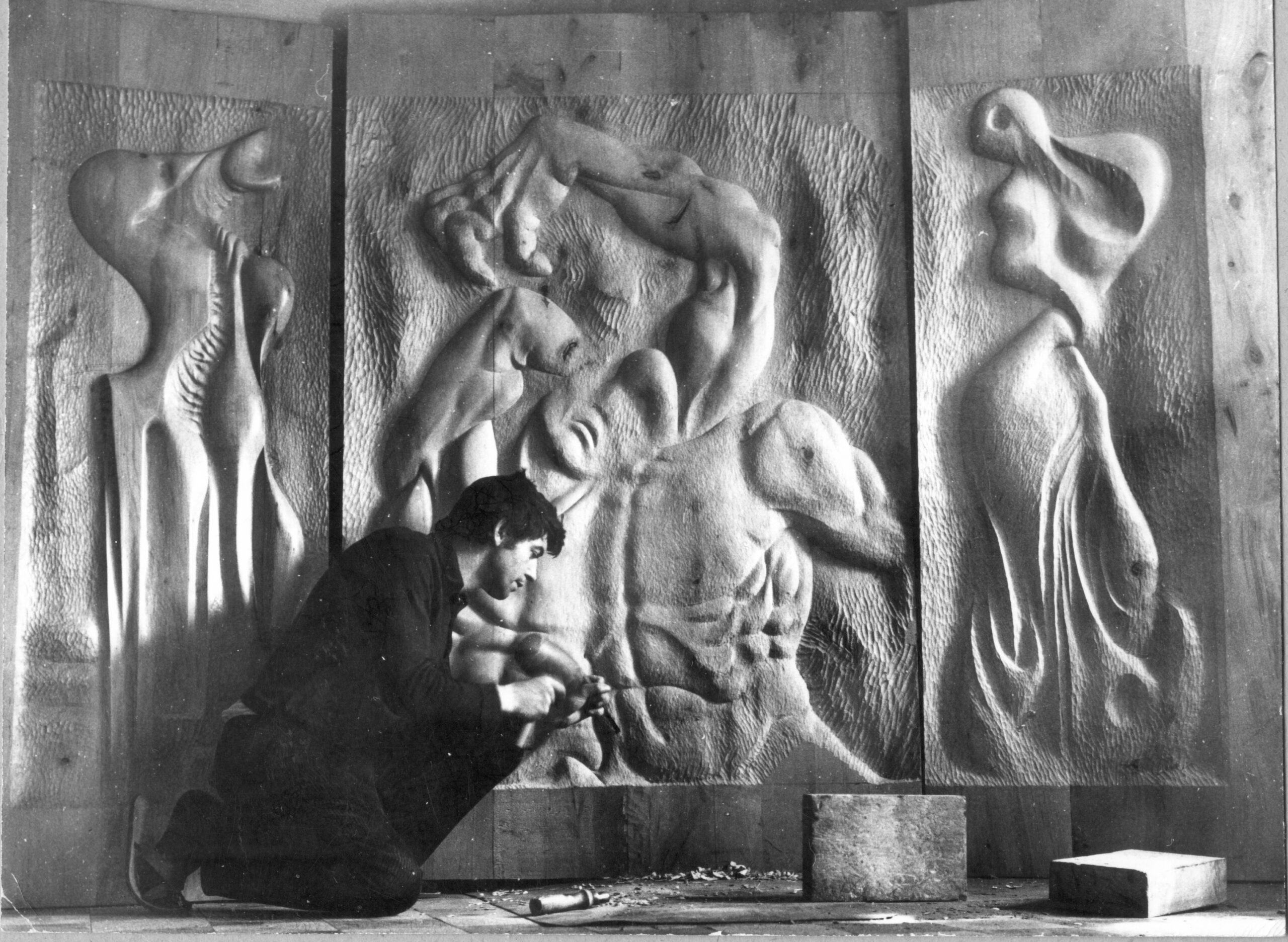

These are the words of sculptor Gyula Bocz, and this is his Ars Poetics at the same time. These words capture a rare moment in the artist’s manifestations because he was known to have shied away from interpreting his works and answering clichéd questions about what they depicted or what and how he expressed himself. He worked purely from inner impulses and drives, he did not make any compromises, and he was not an easy man, it was said. He was driven by a universal inner force to use his chisel and hammer to probe the secrets of wood and stones such as marble, semi-precious stones, and obsidian. Through these elements he explored the secrets of nature. And from this, works of art were born – ad absurdum art as a final result – that became our greatest reward and delight.

His talent, his desire for self-expression, and his strength were already evident in his childhood: the prizes and awards he won in competitions for his works marked the beginning of his development. In his youth, in order to find a paid job, he started working in a machine factory in Pécs. It was here that he first had the opportunity to develop his creativity. In this early period, besides working with metals, he worked primarily with wood. He trained and taught himself, but he was also taught by the artist Ferenc Lantos at the art workshop of the Doktor Sándor Cultural Centre in Pécs. From the early 1960s he began creating organic-nonfigurative sculptures using stone and sometimes metal. The Sea (1964), Flower (1968) and Aspiration (1974) are examples of his sculptures from this period. The concise, sometimes poetic names only partly refer to the visual, but they are typical and vital for understanding his art and its reception. He first exhibited his works in 1963. His surrealist, symbolic, and non-figurative works linked him at the outset with Sürenon artists. However, the rich associations his work evoked in his audience helped him transcend these limiting categories.

He was part of a unique initiative: together with his fellow sculptors, they set up a creative colony in an abandoned quarry on Szársomlyó Hill in Baranya County. This has now become an act of historical significance, as it was the first place in Hungary where sculptors were given the opportunity to experiment freely, independent of styles and trends. Nowadays, you can walk among more than a hundred monumental stone sculptures in the unmined area. Among them is the much talked about epochal Spiral, which refers to the idea of “carving the mountainside.” Gyula Bocz’s desire to probe the secrets of nature began here. The perfect form of the spiral is an ancient symbol of the relationship between life and material, a fact that has been verified by modern science. It is also a symbol of rebirth, as it indicates continuous movement through time.

Stone remained Bocz’s favourite material throughout his life and artistic career. Even choosing the stone became a special act that influenced the creative process, in so far as the primacy of the material could stimulate the artist’s imagination.

The latter is illustrated by one of his most impressive works – a sandstone sculpture entitled “The Electrons of the Atomic Nucleus”, which is a giant sculpture revealing the secrets of the universe. It is currently on display in the Mining Museum in Pécs.

Gyula Bocz was in intimate contact with nature, and under his chisels and grinding tools even the most resistant stone obeyed the will of its creator.

His profoundly intimate relationship with natural materials is symbolized by one of his last works, the story of the Karinthy statue. The stone-carving sculptor selected the rare volcanic stone in Mecsek Hills, known as phonolite (It is an ancient Greek term meaning sounding stone.) He found that this feldspar-containing rock was the most suitable for the bust of the statue, and therefore he began to work with this material. The form had already been outlined when he unexpectedly stopped carving, sensing precisely that a clay vein in the material was blocking his work on the statue’s head structure. If he continued, the stone would burst. He stopped carving and chose a new stone. Unbeknownst to anyone but his immediate family, at the time of working on this project he had to have just undergone the same brain surgery as Karinthy.

In the last years of his life, I was very fortunate to have the opportunity to have long conversations with him in which he expressed his great thoughts on the creative process in his work. I am happy to have known him and I am fascinated by his sculptures. It is good to experience them again on the website dedicated to this profoundly creative artist.

Budapest, 13 June 2022

György Merényi